by Daud Zafar

Introduction to the Church and Christian Community

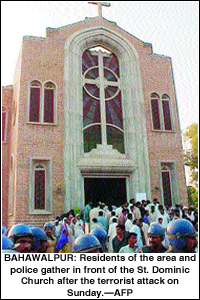

St. Dominic’s Church in Bahawalpur stood as a place of worship and peace for the local Christian community. The city of Bahawalpur, located in southern Punjab, has long been home to a modest but vibrant Christian population. Many of them were workers, teachers, and families who would gather every Sunday to attend Mass, participate in prayers, and celebrate their faith in unity. For the community, the church was not only a spiritual center but also a symbol of their survival and resilience as a minority in a Muslim-majority country.

Government in Power at the Time

The attack took place on October 28, 2001, during the rule of General Pervez Musharraf, who had taken power in a military coup two years earlier. At that time, Pakistan was under intense international pressure, especially after the 9/11 attacks in the United States. Musharraf had allied Pakistan with the U.S. in the so-called “War on Terror,” but within the country, militant jihadi organizations were still very active and influential. This created a volatile situation where extremist groups felt both cornered by the state’s new policies and emboldened to strike at vulnerable targets, particularly religious minorities.

The Attack and the Jihadi Organization Involved

On that fateful Sunday, as dozens of worshippers gathered in St. Dominic’s Church, armed assailants belonging to the jihadi outfit Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) stormed the premises. The attackers opened indiscriminate fire on the congregation, killing 18 worshippers on the spot, including women and children. The massacre was brutal, swift, and left the community devastated. Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, a militant Sunni extremist organization with ties to al-Qaeda and the Taliban, claimed responsibility for the atrocity. For Pakistan’s Christians, the attack was not only a tragedy but also a chilling reminder of their vulnerability in the face of jihadi terrorism.

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi: Origins and Ideology

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) emerged in the mid-1990s as one of Pakistan’s most violent sectarian and jihadi organizations. It was founded in 1996 as a splinter group of the Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP), an anti-Shia extremist movement based in Punjab. The leaders of LeJ believed that SSP’s political activities were not aggressive enough, and they wanted a more militant approach to enforce their rigid sectarian and jihadi ideology.

The group’s founders were:

Riaz Basra – the most prominent face of LeJ, a radical militant who had previously fought in Afghanistan.

Akram Lahori – a key commander involved in sectarian killings.

Malik Ishaq – a notorious figure who later became one of the group’s main leaders and was linked to hundreds of sectarian murders.

LeJ’s purpose and objectives were rooted in violent extremism:

To wage “jihad” against those it declared as enemies of Islam, particularly Shia Muslims, Christians, and other minorities.

To enforce a strict, intolerant version of Sunni Islam inspired by Deobandi ideology.

To maintain close ties with international jihadi networks, especially al-Qaeda and the Afghan Taliban, providing fighters, safe havens, and logistical support.

By the late 1990s, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi had become infamous for targeted killings, suicide bombings, and large-scale attacks on religious minorities. The Bahawalpur Church attack of 2001 was one of its early, high-profile strikes against Christians, carried out as part of its broader campaign of terror across Pakistan.

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi’s Ideology and the Targeting of Christianity

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) and similar extremist groups have systematically distorted the concept of Jihad to justify brutal campaigns of violence against Pakistan’s minority communities, especially Christians. In their radical worldview, Christians are not just a religious minority but are portrayed as “enemies within,” often falsely linked to Western powers or portrayed as agents of the West.

Ideology Against Christianity

The central narrative of LeJ revolves around erasing non-Muslim presence from Pakistani society. Their sermons and propaganda often declare Christian worship places as “centers of infidelity,” thereby legitimizing attacks on churches, Christian neighborhoods, and even individuals in everyday life. For these groups, killing Christians is portrayed as an act of religious purification and falsely elevated to the level of “holy war.”

Funding and Support Networks

The survival and expansion of LeJ has been made possible through a web of financial and logistical support:

Foreign Funding: Radical clerics and wealthy donors from Gulf states (particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE) have historically funneled funds to extremist madrassas in Punjab and Karachi, many of which became recruitment grounds for LeJ militants.

Local Networks: Extortion rackets, smuggling, and underground financial systems (hawala/hundi) also fund these networks.

State Negligence: Although officially banned, LeJ has at times benefited from selective tolerance or indirect patronage by elements within Pakistan’s security establishment, which used them as proxy forces in sectarian and regional conflicts.

The Unstoppable Force Behind Them

The deeper problem lies in the nexus of ideology, money, and politics. The combination of:

1. Gulf-funded radicalization projects,

2. Local clerical networks, and

3. A political-military ecosystem that refuses to decisively dismantle these groups,

…has created a situation where minorities, particularly Christians, remain perpetual targets. The perpetrators kill with the belief that their violence is not only justified but religiously rewarded.

“Jihad” as a Cover for Terror

By labeling their terror as “Jihad,” groups like LeJ turn murder into a sacred duty in the minds of their recruits. This distortion allows them to recruit young, poor, and indoctrinated individuals who are convinced that martyring Christians guarantees them paradise.

Controversial Links: Maulana Tahir Ashrafi and Extremist Networks

Questions arise when observing Maulana Tahir Ashrafi, a prominent religious cleric who publicly promotes peace and interfaith harmony, and his perceived comfort with extremist networks. Reports and eyewitness accounts have noted instances where he has been seen in proximity to individuals linked to jihadi organizations, raising concerns about the nature of these associations.

Critics ask: if Maulana Ashrafi genuinely advocates for peace, how does he maintain such apparent ease with organizations known for sectarian violence and terrorism? This question becomes particularly pressing considering his frequent visits to Gulf countries, including Saudi Arabia, which coincide with funding and support networks for certain madrassas and extremist cells.

These trips are often framed as religious or educational missions, but analysts suggest they may also serve as channels to funnel financial resources into small, strategically planted areas in Pakistan. Such funds can indirectly support the cultivation of jihadi networks, particularly in regions where vulnerable youths are recruited into extremist ideologies.

This dual image publicly a promoter of interfaith peace, privately linked to networks that sustain jihadi operations raises serious questions about accountability and the structural support that allows extremist organizations to thrive under the guise of religious legitimacy.

The Dual Role of Maulana Tahir Ashrafi in the Context of Christian Attacks

Throughout Pakistan, in cities such as Bahawalpur, Quetta, and other regions where Christians have been targeted in terrorist attacks, a curious pattern emerges with Maulana Tahir Ashrafi. Publicly, he presents himself as a protector of Christian communities, visiting affected areas, offering condolences, and appearing alongside victims to convey an image of peace and interfaith solidarity.

However, a closer examination reveals a starkly contrasting reality. Behind this public facade, evidence suggests that he is actively involved in facilitating funding channels for jihadi networks. While appearing to stand with Christian victims, he simultaneously engages with networks that sustain extremist militancy.

This duality raises serious questions about his true agenda. By positioning himself as a mediator and promoter of interfaith harmony, he gains credibility and visibility on the international stage. Meanwhile, the systematic targeting and persecution of Christians inside Pakistan continues unabated. Analysts argue that this pattern serves a deliberate purpose: to project an image of peace abroad while allowing or indirectly supporting the continuation of violence and even what amounts to the ethnic or religious persecution of Christians within Pakistan.

In essence, the public role of peace-broker masks a deeper complicity, enabling extremist networks to operate under the cover of religious legitimacy, while the victims remain trapped in an ongoing cycle of terror and vulnerability.

Daira Sharif and the Role of Family in Extremist Activities

Another dimension to the issue involves the family networks associated with Daira Sharif, particularly Maulana Tahir Ashrafi’s brother. Reports indicate that his brother has been involved in actions that directly or indirectly support extremist operations, including legal and social pressure against minority communities, and in some cases, links to individuals affiliated with jihadi organizations. These actions have raised serious concerns about the role of familial networks in sustaining extremist influence in Pakistan.

Covering Extremist Links Through Interfaith Advocacy

Maulana Tahir Ashrafi, as the public face of Daira Sharif, often presents himself as a champion of interfaith harmony, attending events with Christian and other minority communities, and projecting an image of tolerance and peace. However, critics argue that this public persona is sometimes used strategically to cover or legitimize the activities of family members and networks connected to extremist operations.

This dual approach has significant consequences: while he speaks of dialogue and harmony in public, the voices of Christian communities and other minorities are systematically suppressed. Reports suggest that those who attempt to speak out about attacks, discrimination, or persecution often face institutional pressure, social intimidation, or threats, creating an environment where genuine grievances are silenced.

In essence, the combination of family involvement in extremist networks and the public face of interfaith advocacy enables a form of control over minority communities. It allows extremist activities to continue, while maintaining a veneer of legitimacy and peace that is presented both nationally and internationally.

State Support, Religious Platforms, and International Jihadi Links

When individuals or networks that have been actively involved in the systematic targeting and persecution of Christians receive tacit or explicit support from the state, it raises serious ethical and political concerns. These groups often demand religious legitimacy and official platforms, which they use to impose a narrow interpretation of Islam while restricting free speech and silencing dissenting voices.

Evidence suggests that the web of extremist networks in Pakistan often has direct or indirect connections with international jihadist organizations, including al-Qaeda. The 9/11 attacks in the United States are a stark reminder of how these networks, under the guise of religious struggle, can escalate into global terrorism. While they operate locally under the banner of religion, their ideological and financial links tie them to broader international jihadist agendas.

It is therefore imperative that the state, civil society, and the international community do not allow these groups to impose themselves, do not provide them with funding, and hold them accountable for their actions. Failure to act ensures that these extremists continue their violent campaigns, leaving vulnerable communities to suffer while perpetrators remain unchallenged. The cycle of terror and oppression will continue until these networks are deprived of resources, legitimacy, and safe havens, allowing them to face the consequences of their actions rather than seeing victims starve or perish in silence.

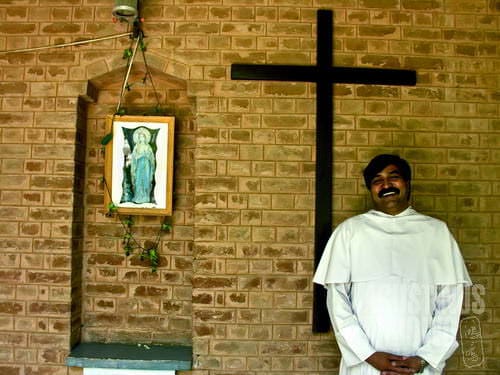

Remembering Father Emmanuel and the Unfinished Struggle

In the aftermath of the Bahawalpur Church massacre, no individual was formally charged, no arrests were made, and no accountability followed—despite the claims of responsibility by militant groups. The silence of the authorities further deepened the wounds of the victims’ families and the Christian community at large.

This article is written in memory of Father Emmanuel, who embraced martyrdom during the Sunday service, standing firm in his faith until his last breath. His unwavering commitment to his congregation and to his beliefs became a symbol of resilience against the forces of hatred and terror. While bullets tore through the congregation, many remember that the attackers’ eyes turned away in haste, unable to face the dignity and courage with which Father Emmanuel and his flock endured their final moments.

Yet, the tragedy of Bahawalpur was not the end. It marked the beginning of a pattern of violence that continued in Quetta, Peshawar, Lahore, and beyond. Each attack deepened the scars, revealing the systematic nature of persecution and the absence of meaningful state protection for Pakistan’s Christian minority.